HISTORY OF WILDERGARDEN

On yielding to nature with passive restoration:

“Nature can be trusted to work her own miracle in the heart of any man whose daily task keeps him alone amongst her sights, sounds, and silences.”

In 1990, Julia Wilder purchased the property that would become Wildergarden, a 0.13 acre yard on a residential parcel of land in north central Indianapolis, Indiana. It sits on Miami soil, a forested loam soil that formed after the glaciers receded. Copious amounts of forest debris blended with the ground rocks (glacial till and outwash) to make one of the richest soil belts on earth.

The Origin of Wildergarden

With knowledge of Wildergarden’s ancestral soil, Julia set out to grow vegetables on a 10 by 10 foot garden plot that was rototilled. Nature had other plans! She immediately saw shifts in insects and wildlife and decided to yield to Nature instead. The project proceeded with the removal of additional sod cover by rototilling. This was followed by the input of composted horse manure from a local stable, straw from local farms, and deciduous tree leaves. This jump-started soil health with additions of organic matter and earthworms. Cover crops of winter rye have further aided soil health.

Transformation from turf grass yard to wildlife sanctuary

In the Beginning

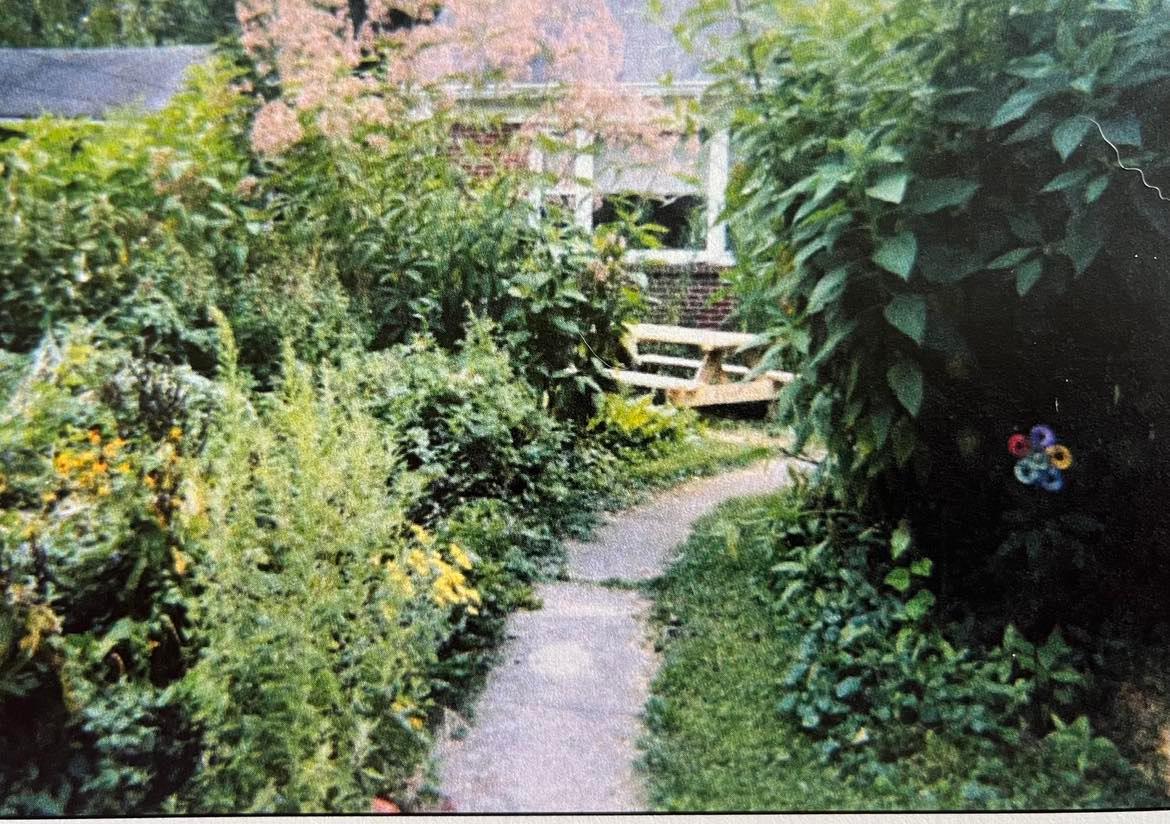

The Wildergarden process is experimental and constantly evolving. Because it occurs on a small fragment, it has what biologists call the “edge effect.” It is not deep forest. The entire space is like a forest edge. One exciting result is that biodiversity increases quickly. New organisms (plant or animal) can migrate in without having to go a great distance through barriers or predators.

Populations of forest ecology plants, birds and mammals have volunteered at each successive stage of the project. When Wildergarden was founded, we had 5 trees, of 3 species, and non-native shrubs and ornamental flowers installed by previous owners. The birds visiting the feeders were robins, cardinals, blue jays and red finches.

What We Did

Agricultural planting, year by year, of supplemental native trees, shrubs, wildflowers, grasses and sedges have provided additional layers of canopy and soil cover. Over the years, most of the woody and herbaceous biomass grown here has been recycled back into organic soil matter. This means that all dead and discarded plant materials stay here. Our job has been to keep it looking intentional, organized and relatively tidy. We have also added straw and tree leaves from neighbors onto our soil on a regular basis.

Wildflowers that have volunteered at Wildergarden beginning during the prairie phase included: wild violet, beggartick, white snakeroot, woodland knotweed, and pilewort. Wildflowers we have planted and are growing successfully include: Wood (Celadine) Poppy, Wild Geranium, Jacob’s Ladder, Downy Skullcap, Mayapple, Cup Plant, Red trillium, Virginia Bluebells, Variegated Solomon’s Seal, and Small White Aster.

At earlier stages of succession, we had volunteer grasses, such as foxtail. We also planted Northern Sea Oats, Beak grass, and Bottlebrush Grass. We also planted Bur sedge and Oak sedge.

All of our various fungi are volunteers.

Where We Are Now

At the present state of its transformation from a turfgrass lawn, Wildergarden is populated by native hardwoods and conifers, and currently exhibits the young forest stage of succession. Since those early days, oaks (red and burr), green ash, hackberry, wild cherry, eastern redbud, sweet gum, beech, walnut, eastern red cedar and silver maple have all emerged from the soil (without human planting). The native trees we have planted to enhance the biodiversity are: River Birch, Yellowwood, Pignut, Hickory, Paw Paw, Persimmon, Northern Pecan, Red Horsechestnut, White Oak, Red Oak, Northern Catalpa, Serviceberry, White Pine, and Eastern Hemlock.

This transformation of Wildergarden is an example of gradualism, in which natural change occurs slowly (but surely). The personal qualities of patience and forbearance in the land steward have been essential to our success over the last 3 decades and counting.

Baby eastern red cedar emerging from the ground. This species is our only native evergreen tree.

In 2021, we inventoried 271 trees of 38 species. Most are verified native to Indiana and the majority (67%) are volunteers. That is an increase of over 5300% in the number of trees in 30 years! Click HERE to see the methods and complete results of the Tree Inventory.

In 2023, we documented 25 species of bird visitors and/or residents who use our habitat, an increase of over 500%! We also had other birds at earlier stages in succession. Click HERE to see the results of Wildergarden’s participation in The Great Backyard Birdcount.

Forest fragment for lawn replacement

Marion County Soil Survey

The Marion County, Indiana Soil and Water Conservation District (MCSWCD) published a detailed report on the county’s natural resources in 1978. The complete soil survey is available HERE. At that time, 25 percent of local land use was farming. The report states that Miami soil “is well-suited to lawns, vegetable and flower gardens, and shrubs and trees.” It added: “Erosion is a problem in disturbed areas where the slope is 2 to 6 percent are left bare for a considerable period.” (Soil Survey p. 22)

At Wildergarden, we understand that one of the purposes of lawn sod is to prevent soil erosion. However, this monocultural ground cover holds natural soil functions in check and prevents nature restoration. The sod prevents water and air exchange with the atmosphere and is a barrier that blocks organic matter such as plant litter from contacting the soil surface where it would form humus.

The opportunities for sustainable land use abound in the report. It states: “Woodland habitat consists of hardwoods or conifers or a mixture of both, and associated grasses, legumes and wild herbaceous plants.” Among the native wildlife expected are thrushes, nuthatches, woodpeckers, squirrels and raccoons. (Soil Survey p. 47)

Wild herbaceous plants are “native or naturally established grasses and forbs, including weeds, that provide food and cover for wildlife.” Examples include ragweed, beggartick, goldenrod, poke, lambsquarter, and knotweed. “Hardwood trees and the associated woody understory provide cover for wildlife and produce nuts or other fruit, buds, catkins, twigs, bark or foliage that wildlife eat.” Examples given of native woody plants include oak, hickory, beech, maple, poplar, wild cherry, sweetgum, basswood, dogwood, hazelnut, wild grape, blackhaw viburnum and black walnut. Coniferous plants are mentioned as providers of habitat as well. It mentions smartweed and sedges as wetland plants that grow on moist or wet soil (common in historic Indiana). (Soil Survey p. 47)

In sum, Wildergarden is a reflection of our county’s natural heritage.

A Diary of Wildergarden: My Wild Yard in the City

Want to know even more of the story of the first decade of Wildergarden? Founder Julia Wilder wrote a book about process of transforming her land from a traditional grass lawn to a certified wildlife habitat!

A Diary of Wildergarden: My Wildyard in the City tells the story of a contemporary woman who bought a home in a city neighborhood, complete with a traditional grass lawn, and describes how she transformed the grass and soil into a vibrant natural garden. Doggedly overcoming conflicts with neighbors and a county health code, she ultimately succeeds in her task and life is good amidst her bird-filled oasis. Wildergarden is a certified wildlife habitat comprised largely of native wildflowers, bushes and trees, and is a tribute to Nature in all its glory.